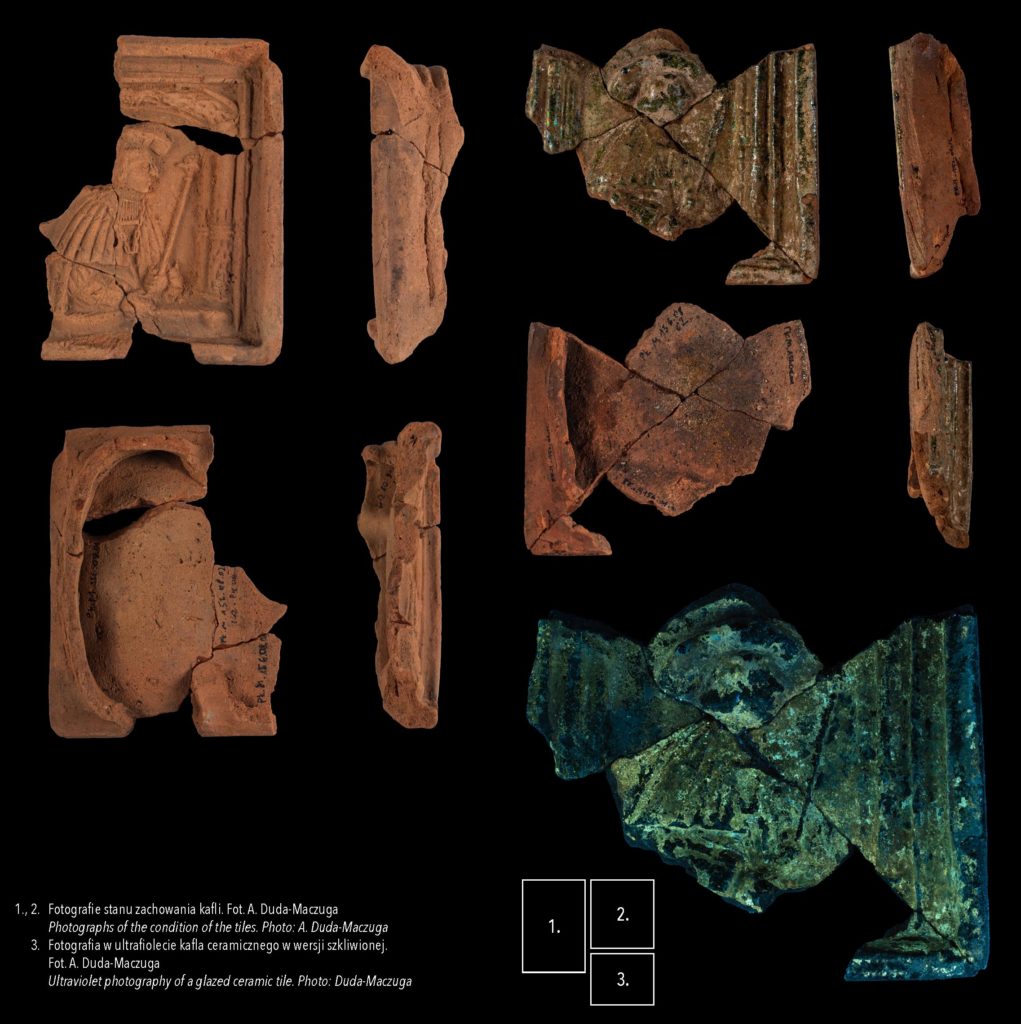

Photography has accompanied conservationists from practically the very beginning of their work. The most obvious purpose of photographing a historic site is to visually record its state of preservation, both before, during, and after maintenance activities. It is, therefore, part of the documentation process, no less important than the descriptive part.

The key during this process is to accurately portray the subject being photographed. This may seem relatively simple because it requires capturing an image of an existing object rather than using artistic expression. Photography, however, is the encapsulation in a fraction of a second of a whole range of optical, electronic, and once even photochemical processes. Taking a picture that faithfully reflects the historic object requires knowledge and preparation in order not to disturb the proportions or perspective with unwanted optical aberrations. The procedures for photographing, but also reading what is included in the photograph, should be universal for conservators and art historians around the world. The photos should be 'decodable’ in a precise, scientific way, so that the documentation will be legible not only for the recipient on the other side of the globe, but also for those viewing the photos in a few decades.

Such a photograph is a time machine. It allows you to stop time and move the image of the subject being photographed many generations ahead.

It is our professional descendants, in a few decades or even centuries, who should be able to easily see what an object looked like before and after a previous maintenance process to restore it to its historical condition. We carefully search and benefit from the wealth of preserved archival photographs ourselves. Recognizing their shortcomings due to the technical limitations of our predecessors, we try to create the best possible database for our successors. Then there is photography which has no ambition of time travel but brings us closer to a gaze more penetrating than that of the preservationist. Even the most experienced eye of a specialist has no chance to see everything.

What do you need to see? Today, we know better what affects the state of historic preservation. What destroys it. And we know how to stop or reverse these processes. Largely because we can see what the naked eye cannot see.

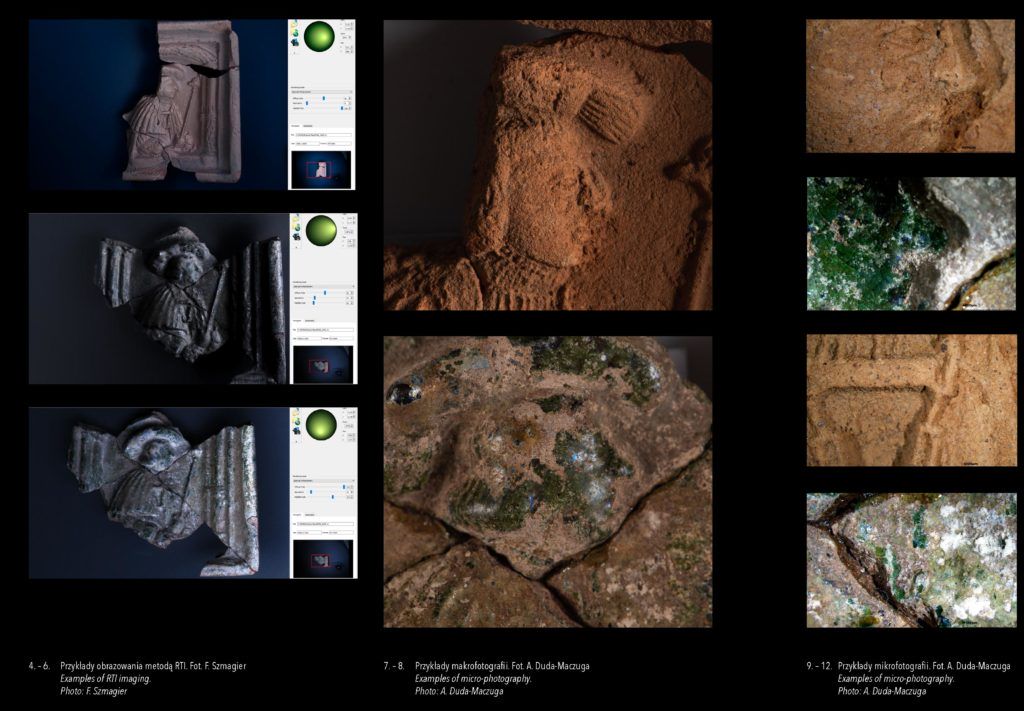

To take detailed photographs of ceramics, optical systems are used that allow for high magnification to get a better look at the details. With the help of macro- and micro-photography it is possible to know more, fixing the surface of the monument virtually to acquire measurement data that would be impossible to measure with traditional tools.

Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) belongs to computational research methods. It uses appropriately taken photographs to create a virtual model of the monument. During its later viewing, it is possible to change the parameters of the angle of incidence of light and its intensity, and other modes and functions showing the details of the surface and the modeling of the monument.

One more technique used in conservation photography is fluorescence testing and ultraviolet (UV) photography. This is based on the ability of some materials to absorb some of the electromagnetic radiation from the visible ultraviolet region and then emit less energy as visible light. This can sometimes provide additional information about the object being observed.

Such photography helps conservationists become more familiar with the objects they work on. It also perfectly complements conservation documentation and proves that often the photo really is worth more than a thousand words.

Anna Duda-Maczuga

The Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw